AI in recruiting: Why the AI Boom Is Turning Entry-Level Hiring into a Bust

There is no doubt AI is here to stay. Recent reporting highlighted that Anthropic, a startup that did not exist six years ago, has valuation chatter putting it in the range of the world’s largest consumer brands. Executive pay packages tied to AI leadership are becoming staggering—one report put the pay for a top AI executive moving from Apple to Meta north of two hundred million dollars. These headline-grabbing facts underline a broader economic reality: leaders of powerful firms expect a tidal wave of change. They are preparing for it, and for many jobseekers—especially those at the bottom rung of the career ladder—the effects are already visible.

What’s particularly striking is a statistical anomaly that has no parallel in the last 45 years: the unemployment rate for recent college graduates has climbed above the unemployment rate for all US workers. Historically, recent graduates enjoyed lower unemployment than the general population; today they don’t. That inversion is an alarm bell. And while multiple forces are at work—post-pandemic cooling of hiring, shifting demand across industries—AI in recruiting appears to be an accelerating factor.

The candidates: accomplished, prepared, and still struggling

Take two graduates profiled in the original reporting: Tiffany and Jacob. Tiffany studied information science and psychology at Cornell, secured internships at Apple, and built a compelling portfolio that included contract roles and campus club projects. Jacob majored in economics and finance at Boston College, completed in-class discounted cash flow and leveraged buyout modeling exercises, and interned at a boutique private equity firm. Both did what the conventional career playbook prescribes: good grades, internships, networking, and demonstrable skills.

And yet, after graduation both have struggled. Tiffany described applying to roughly two hundred roles; Jacob has similarly high application counts. They advanced deep into processes—final rounds, multiple-stage interviews requiring valuation models and pitch decks—only to be rejected, ghosted, or left in limbo. Their experience is now common, and it’s being reflected in job-posting and unemployment data.

Data points: junior postings fall even as senior openings rise

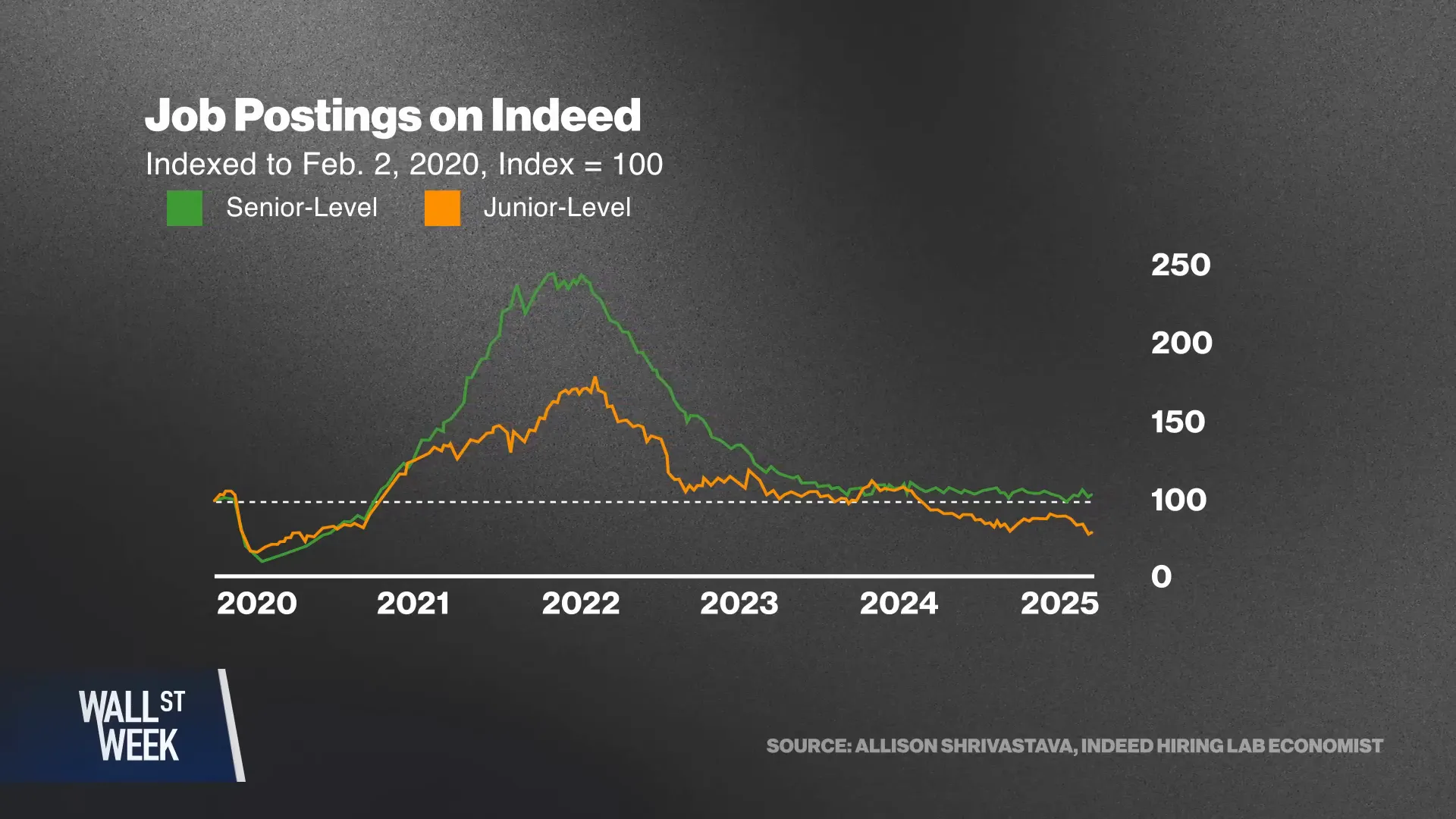

Company-level hiring data paints a clear picture. Analysis by Indeed for Wall Street Week found that junior-level job postings are down about 21% from pre-pandemic levels, while senior-level job openings have increased. In other words, firms are hiring higher up in the organization even as entry-level opportunities dry up. That trend is visible in industries that historically absorbed large numbers of new graduates: tech, finance, and legal services.

This change in the composition of hiring speaks directly to how AI in recruiting and AI-driven productivity gains are being implemented. Automation and augmentation can reduce the need for routine junior tasks—data entry, first-draft analysis, basic modeling—and companies appear to be rebalancing headcount toward more experienced employees who can govern and amplify AI systems.

How AI in recruiting is changing the nature of entry-level work

Executives and economists have been both blunt and nuanced about what AI implies for employment. Centerview Partners cofounder Blair Efron told us AI is progress and, over the long haul, will be beneficial. But he warned the short-term impact on employment could be “dramatic sooner than we think.” That combination—long-term promise, short-term disruption—captures the dilemma facing new graduates entering a market where AI in recruiting and operations reduces demand for routine junior labor.

"AI is progress. Over the long haul, it'll be good. In the short term, I have big concerns. I believe the impact on employment is going to be dramatic sooner than we think."

AI’s capacity to perform first-draft tasks, synthesize data, and even produce polished outputs that once required a human junior analyst makes it especially impactful on early-career roles. Employers can now use AI in recruiting to screen candidates, generate initial analyses, and routinize tasks that would previously have required hiring many junior employees. The result: fewer entry-level roles available and higher bar for the ones that remain.

Examples of tasks affected

- Resume screening and initial interviews automated by AI systems.

- First-cut financial models, draft memos, and basic legal research handled by AI tools.

- Design mockups and routine coding tasks generated or assisted by generative models.

These shifts do not mean the end of hiring, but they do mean hiring priorities change. Firms may prefer mid-career hires who can integrate AI outputs, exercise judgment, and provide oversight. That leaves new graduates in a tight spot: plenty of ambition and skill, but fewer roles where they can learn on the job.

The distributional effects: who bears the brunt?

The impact of AI in recruiting and hiring isn’t uniform. Recent college graduate unemployment has risen overall, but the increase is concentrated among men. Why? Because women disproportionately enter fields—health care and education—that are still hiring. Men are more likely to enter computer science, tech, and finance, which are the sectors experiencing the highest AI adoption and the sharpest declines in entry-level openings.

AI Agents For Recruiters, By Recruiters |

|

Supercharge Your Business |

| Learn More |

Matthew Martin, a senior economist at Oxford Economics, points out this occupational mix explains much of the gendered outcome. Where female graduates move into healthcare and education—sectors with robust demand—male graduates cluster in fields exposed to automation and AI-driven efficiency gains.

What graduates can do: practical advice and skills to prioritize

The executives we spoke with offered concrete guidance. The refrain was consistent: stay flexible, broaden your skill set, and invest in capabilities that remain uniquely human. That includes:

- Critical thinking and judgment: the ability to synthesize facts, question model outputs, and provide reasoned conclusions.

- Communication and writing: clear, persuasive writing remains a scarcity that AI does not fully replicate.

- Interpersonal skills: collaboration, negotiation, and empathy for roles where human interaction matters.

- Curiosity and adaptability: the art of learning new tools and disciplines as firms adopt AI in recruiting and operations.

One executive put it succinctly: "Taking a lot of writing courses, a lot of humanities, learning how to think critically, learning the art of learning... judgment's not going out of style." Those are the attributes that will help graduates compete in a labor market where AI is part of the toolset.

Choices and trade-offs: master’s degrees, bootcamps, or alternative pathways?

Faced with a tougher entry market, some graduates consider returning to school. For many this is a fraught calculation: a master’s degree can delay the job search and add significant cost, but it can also offer a bridge to new skills and, in some cases, a higher signal of employability. Alternatives include targeted reskilling—coding bootcamps, data analytics certificates, or specialized training in areas where AI complements rather than replaces human labor.

Whatever the path, the reality is clear: employers are changing how they recruit, and AI in recruiting is part of that change. Graduates must adapt by choosing fields and skills that are likely to grow in demand—roles emphasizing judgment, creativity, and interpersonal capability.

Policy and corporate responsibility

The broader economy will feel both the benefits and the costs of AI. Policymakers and corporate leaders face choices about how to manage transition pains: retraining programs, incentives for on-the-job learning, and measures that ensure firm-level productivity gains do not translate into long-term unemployment for cohorts entering the workforce. The conversation is starting, but it needs to accelerate.

Conclusion: the rules have changed—now what?

Tiffany and Jacob did everything the conventional advice recommended: strong academics, internships, networks, and specialized skills. Yet they find themselves contending with structural shifts: post-pandemic recalibration of hiring plus the rapid integration of AI in recruitment and work processes. The rules for launching a career have been rewritten in ways that are still unfolding.

AI in recruiting is not a single event but a process. Over time, it will reshape hiring, job design, and the skill sets employers prize. For graduates today, that means prioritizing human strengths AI cannot easily copy: judgment, critical thinking, writing, and interpersonal skills. It also means being pragmatic about career pathways—considering industries in growth mode, exploring alternative credentials, and building resilience in a market that is evolving fast.

The long-run benefits of AI may well dwarf the short-term dislocations. But when you’re in the middle of the first job search, the long run can feel distant. The practical response is immediate: widen your aperture, invest in uniquely human skills, and be prepared to navigate a labor market where AI in recruiting and workplace technology is the new normal.